by Ronald M. Johnson On January 16, 1986, Coretta Scott King unveiled a memorial bust of her husband in the … More

Author: U.S. Capitol Historical Society

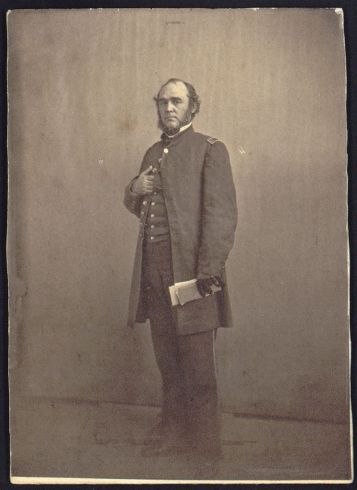

Montgomery Meigs’ Vision of Arlington Cemetery

–by Ronald M. Johnson Among the individuals who played prominent roles in the building of the United States Capitol was … More

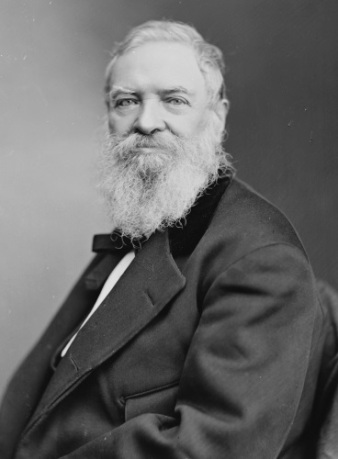

The Temporary Insanity of Rep. Daniel Sickles

–by Clare Whitton, USCHS intern On a chilly winter evening, U.S. Attorney for the District of Columbia, Philip Barton Key … More

George Washington’s First Principles of Executive Leadership

Editor’s note: On Wednesday, August 3, our summer lecture series continues with Dr. Kathleen Bartoloni-Tuazon’s book talk about her recent … More

Constantino Brumidi: Immigrant or Refugee Pt. 2

We’re marking the anniversary of Brumidi’s birth by revisiting remarks from a 2015 celebration. See here for Part 1. –by … More

Constantino Brumidi: Refugee or Immigrant?

–by William C. diGiacomantonio To mark the 211th birthday of the Capitol’s premier artist, Constantino Brumidi, we are posting the … More

Francis Doughty: Visionary or Trouble Maker?

Today we welcome Mau van Duren to the USCHS blog! He will be discussing his new book, Many Heads and … More

Government Girls

UPDATE: Gueli’s talk has been rescheduled, for Wednesday, May 18. See our website for more information about her book. On … More

Capitol Apples

–Shana Klein, Ph.D., Art History, University of New Mexico; USCHS Capitol Fellow March 11 has been declared National Johnny Appleseed … More

Mary McGrory, Congressional Columnist

Editor’s note: On Thursday, March 10, the U.S. Capitol Historical Society will host author John Norris in conversation with Don … More